It is tempting to dream of two distinct moments in the history of tourism: Tourism B.C. and Tourism A.C. (“Before” and “After Covid”), marking 2020 as the year of the rebirth. In the first period, tourism would be described basically as a predatory industry of natural and cultural resources, responsible for a huge global carbon footprint, generating socio-economic imbalances in the receiving communities, strongly based on intensive labor and precarious jobs, and causing various types of paroxysms such as gentrification, so-called “overtourism”, enclave tourism, etc. And, as if that were not enough, it was tourism that, most of the time, provided unsatisfactory and low value experiences.

Instead, the second period – Tourism A.C. – would be praised for having suppressed the great evils of tourism of the previous period, regenerating it at its core in order to make it an important factor of human development, a guarantor of the improvement of the quality of life of the host communities, providing reviving and culturally uplifting experiences for tourists, stimulating creativity and the true encounter between cultures, and at the same time offering conditions of dignity to workers in the sector.

But, though well-intentioned, such a dream of change is clearly simplistic and naive, and no Manichaeism of any kind will help to detect the best ways to seize the new opportunities that may emerge in this new phase of society’s development. Nonetheless, there is still a sense in distancing and confronting the “good” and “bad” scenarios of tourism development. And no matter how idealistic it may seem, it is increasingly important to strive for better models of tourism organization in order to align this important industry with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals advocated by the UN. The aim of this article is precisely to present some benchmarks for building a new tourism in the post-Covid-19 era.

The apology for smooth tourism symbolized by the formula “Slow, Smart & Small”

In April I advocated the advent of a new approach to sustainable tourism, and suggested redefining the “3Ss” formula (instead of “Sun, Sea & Sand”, I proposed the new “Slow, Smart & Small” model). This approach is based on the basic assumption that the essence of tourism lies in the search for meaning (meaning of life, more exactly). And this search for meaning corresponds to an intimate drive that is expressed in a predilection for more authentic and genuine experiences, more relaxed sociability, a preference for creative activities, and also the search for experiences that foster the living of spirituality.

This proposal has been drawn up on the basis of two fundamental premises, the validity of which serves as an anchor to outline a set of ideas that I shall present in this article. These are the two premises:

- From the point of view of socio-economic and environmental sustainability, comparing the massified tourism model with a smoother tourism model (i.e. small-scale, less frenetic and dispersed throughout territories), it is unquestionable that the latter can offer better quality products and services to visitors/tourists seeking meaningful experiences through the consumption of more authentic local products, and is therefore a more rewarding type of tourism for both local communities and tourists. And even from an economic point of view, a smooth, small-scale tourism that invites slow and intelligent immersion in territories and communities can also be considered as a great business, being able to guarantee in the long term greater profitability and a higher level of distributive equity than the still dominant models of mass tourism.

- All decisions on sustainable tourism development are ultimately ethical in nature, as they refer to the reduction of negative impacts, the fair sharing of benefits and intergenerational equity, i.e. the preservation (and/or enhancement) of natural and cultural resources so as not to mortgage the quality of life of future generations. It therefore makes perfect sense to speak of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ models of tourism.

Consequently, if we really strive for sustainable tourism, our scrutiny and our critical sense must focus primarily on the actions of public decision-makers and businesses, leaving aside consumer behavior as irrelevant. In fact, it is irrelevant or even absurd to blame tourists for the structural problems of tourism, creating dichotomies between “good” and “bad” tourists (incidentally, we consider it illegitimate to pass judgment on legitimate consumer choices, even if we do not like them). On the contrary, tourist destination management bodies (DMO), if they are competent, know that there are models of tourist development that are harmful to the environment and harmful to the development of local communities, and that there are alternative models that are more beneficial and have less negative impacts on both the environment and indigenous communities. Furthermore, it is up to the DMO to decide which tourism products their destinations should promote and which types of tourism developments can be licensed. It is the responsibility of the DMOs to define priorities and lead the tourism planning process.

Therefore, assuming that the two premises mentioned above are correct and that they reflect the reality of tourism today, it makes sense to go further and outline some proposals or benchmarks, which will help to consolidate the new model of soft/smooth tourism, by providing its promoters not only with the appropriate arguments, but above all with the criteria that will enable them to facilitate and make its practical implementation more tangible. I will try to structure my proposals on the basis of the following three benchmarks:

- The social responsibility of public decision-makers;

- The infrastructure to support new models of tourism development;

- Creative tourism as a prototype for the new Slow, Smart & Small tourism.

The social responsibility of public decision-makers and academic experts

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) consists of the adoption of voluntary practices by companies in order to promote the well-being of their internal and external stakeholders. Such concept emerges from the notion of citizen company, which is willing to contribute to the common good, going beyond what is formally required in legal terms. Companies and organisations that show high performance in terms of social responsibility tend to gain a greater reputation among local communities and consumers, which in turn favours the good-will of the company/organisation brand.

I believe that the time has come to encourage the scientific community, NGOs and more aware citizens to adopt a critical sense and to carefully scrutinize the decisions of the DMOs, based on the criteria of CSR, specially in cases where their decisions are crucial for tourism development. The political and social responsibility of the DMOs is particularly relevant to tourism planning and destination management, particularly in the areas of project financing, tourism licensing, territory governance and destination promotion.

As it is well known, financial resources are invariably scarce. Therefore, it is essential to define clear priorities on the type of projects that should be supported. And the rule should be simple and transparent: creative and innovative projects, aligned with sustainable development plans, should be strongly supported; instead, harmful or even toxic projects from a sustainable development point of view should be rejected outright.

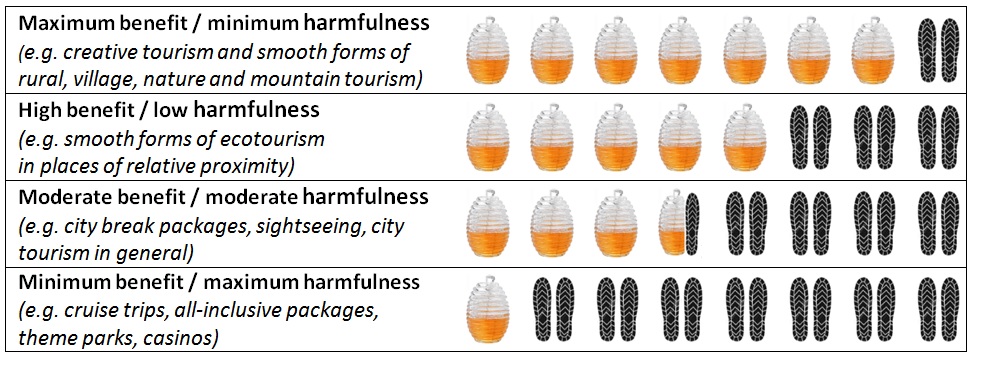

Therefore, universities, international organisations and research centers should join forces to propose a sort of “ranking of toxicity” of tourism products. In my opinion, it makes sense to parameterise the level of environmental and socio-economic efficiency of each tourism product and make this information available to the consumer. Just as the energy efficiency of household appliances is presented to consumers (ranging from A++ to D), in tourism it will also be possible to categorise the levels of benefits and damage that each type of tourism product can cause. By way of example: in terms of benefits and damage to society and the environment, a stage of rally race championship and a nature tourism project are not on the same level. And the decision to support a rally race over a nature tourism project will reveal the level of CSR of the respective DMO.

However, even in the absence of a metric or categorisation system to qualify the environmental and socio-economic performance of each type of tourism product (e.g. a continuum whose extremes would be the classifications of ‘highly beneficial’ and ‘highly toxic’), any common sense assessment reveals significant differences between the different options for tourism development. For example: an apitourism project (beekeeping-related tourism) is at the opposite end of a kart racing project. In the same way, we can oppose city sighteseeing tourism and creative tourism as being in opposite poles, regarding their benefits and negative impacts.

As a kick-off and a kind of provocation to my colleagues at the academy, I then present a draft bipolar ranking of tourism products according to their degree of benefit versus harmfulness to the host communities and the environment. The negative pole of the continuum is represented by a large “carbon footprint” (or many footprints), the most positive pole being represented by a large “honey pot” (or many honey pots). The following figure is just a generic representation of the model I advocate, and I present it as a challenge to the academy, calling on all my colleagues to take sides in favour of more sustainable tourism products.

I therefore believe that a classification system of the impacts of tourism products, based on a bipolar scale of benefit versus harmfulness levels, will enable a reference system to guide the decisions of both public decision-makers and consumers/tourists. In addition, the use of the figure of “honey pot” will allow to moderate the critical discourses on tourism, totally based on the figure of “carbon footprint”, ignoring that tourism also has positive impacts, which vary from case to case.

But even in the absence of a classification system, the DMOs cannot divest themselves of their responsibilities, as it is up to them to lead and guide tourism development in a particular direction. And the “best direction” has universally recognised benchmarks: the 17 UN sustainable development goals (SDOs). Thus, each DMO must be careful in defining the profile of the destination, and selective in defining the range of strategic tourism products, so as to ensure intelligent and sustainable use of endogenous resources, aimed at improving the quality of life of local communities.

Furthermore, being the tourist destinations “great orchestras” where the various musical instruments are in the hands of numerous “stakeholders”, each DMO has to create a functional “score” that ensures the collective harmony as a condition for success, that is, to be able to produce a creative tourist offer of great value to its consumers. In this context, a posture of transparency, dialogue and networking are some of the most valuable qualities of any DMO. It must also have the ability to assimilate and adopt the scientific and technical knowledge that is required for a modern and competent management.

And given the complexity of the tourism system, DMO cannot forget that they have a compass that helps them to stay on course: ultimately, all their activities must have as a corollary the quality of life of the host communities and, concomitantly, the satisfaction of tourists. It follows logically from this that tourist investment options that do not contribute to the valorisation of endogenous resources and the improvement of the quality of life of local communities should be rejected outright, even if they appear to be sustainable by any greenwashing or economic proselytism.

It is precisely when they have to arbitrate between conflicting options and goals – investors’ interest versus the superior interest of local communities – that the performance of the DMOs in terms of social responsibility becomes more evident. And, curiously, such ethical dilemmas are much more frequent than some well-meaning but naive minds might imagine. And, unfortunately, there is no independent body to assess the adequacy and public interest of the decisions taken by the DMOs. So, I repeat, it is time for the academic community to assume its own social responsibility by systematically and more rigorously scrutinising the kind of decisions that are made by the DMOs, rather than simply flattering the power, as in most cases.

Support infrastructures for new tourism development models

For a century, governments have shown extreme generosity in promoting mass tourism by financing its infrastructures (appropriate legal system, tourism plans, urban plans, marinas, cruise ports, airports, etc.).

These government supports fit into the traditional logic of top-down regional development (i.e. a model of concentrated development geared towards spatial zoning of economic activities, using factors and resources from outside the regions that are intervened, based on decision criteria that are also defined outside those regions). However, this logic is gradually being replaced by a bottom-up orientation that seeks to overcome regional imbalances through not only attracting external resources and factors, but mainly through the intelligent and sustainable use of the territories’ endogenous resources, based on decision criteria of the local actors themselves.

In addition, bottom-up approaches have been found in recent decades to best suit the requirements of sustainable tourism. In Portugal, as in many other European countries, there are numerous success stories that confirm the vitality and advantages of the endogenous regional development model. Here are just a few good examples related to different tourism products: village tourism projects (e.g., Schist Villages network, Historical Villages network and mountain villages network, etc.), nature tourism projects (e.g., Arouca Geopark or Geopark Estrela), cultural tourism projects (e.g., Eco Museum of the Barroso or Romanesque Route) or also, in the field of astronomical tourism, the Dark Sky Alqueva project. Due to their singularity and capacity to arouse authentic experiences, all these projects are national and international references and all of them have some similarities that are worth mentioning, namely:

- are projects promoted and coordinated by organizations that operate in a network, aggregating wills and creating a positive social identity, which facilitates the union of efforts towards a common purpose;

- they structure the entire tourist offer around the safeguarding and promotion of a certain endogenous resource (historical-cultural or natural heritage), and from this unique and differentiating resource they promote the region as a destination brand;

- they offer unique experiences to visitors/tourists, while making many businesses possible and attracting new entrepreneurs to the territory.

But while they can be an excellent alternative to the mass tourism products that are dominated by the titans of big global industry, the local tourism products, whose humus are the endogenous resources, are still in a larval stage of their evolution, and their infrastructure is still very fragile, so they need government support to consolidate themselves as a real alternative. And while it is true that for decades governments have invested abundantly and generously in infrastructure to support “heavy” mass tourism, it is also true that those same governments have been too parsimonious or even reluctant when it comes to supporting soft/smooth tourism projects that are emerging from the new dynamics of bottom-up development.

Such a discrepancy in government support for locally based tourism projects can even be considered an injustice, especially in relation to local communities who persist in living in low-density territories, revitalizing them and keeping alive the ancestral traditions of remote villages. It is these people who best provide the alternative for new tourism. However, no form of tourism is consolidated by spontaneous generation without the dedicated and systematic support of public entities. In fact, for endogenous development to occur, three conditions must be met simultaneously:

- to have someone with the will and capacity to organize the means of production, that is, to have someone with a good project;

- the existence of material and institutional conditions that allow this project to be realized;

- the existence of organizational capacity that guarantees competitiveness in the market.

It is the responsibility of governments and DMOs to create the enabling institutional ecosystem for local-based tourism products to flourish. In particular, public entities should invest in a consistent and permanent way in training local actors, giving them the skills to innovate, create and/or modernize their businesses. In this respect, the CREATOUR project, which I will mention below, is a brilliant example.

Creative tourism as a prototype for the new “slow, smart & small” tourism

Creative tourism has emerged as a reaction against mass cultural tourism. Its genesis is linked to the growing need of consumers who are looking for more authentic, engaging experiences and who express the desire to cultivate their own creativity through tourism. The creative tourism approach enables both parties – visitors and host communities – to benefit equally from tourism by integrating the host community’s artistic and creative activities into the process of socio-economic development and thus promoting the vitality and cultural sustainability of the territories.

Creative tourism offers visitors the opportunity to develop their creative potential through active participation in workshops, courses and other learning experiences that are characteristic of the tourist destination they visit. It is a new form of tourism in which natural, cultural and personal resources are not exploited, but rather valued and optimized, giving rise to a new development paradigm in which the tourism industry collaborates with local actors among the most diverse: farmers, artists, craftsmen, cultural managers and others.

In order to develop and implement an integrated approach to creative tourism in small towns and rural areas of Portugal, the CREATOUR project was implemented, and its methodology included four key dimensions: active participation of visitors; creative self expression; learning; and immersion in the local community.

Implemented between 2017 and 2019, under the leadership of Nancy Duxbury, the CREATOUR project involved five research centres that worked in a network and in close collaboration with several dozen organisations, located in small towns and villages of four Portuguese regions: Northern, Central, Alentejo and Algarve. A total of 40 pilot initiatives were carried out to monitor the processes, results, problems and impacts of creative tourism activities on promoting entities and local development. In order to relate creativity to the place where it happens and to complement the development of the pilot initiatives, several reflection and experience sharing meetings were held – the so-called IdeaLabs. A training and consolidation plan for networks and clusters was also implemented, focused on the development of strategies and measures for post-project sustainability. The following video helps to better understand all the general dynamics of the CREATOUR project:

Additionally, this project demonstrates the virtuosity of the relationship between universities and local communities, and the transfer of knowledge and innovation should be considered as an important assets of tourism development at local and regional level.

The CREATOUR project is a great example that it is possible to pave a new way to build a truly sustainable approach to tourism in European countries, which condense millennia of culture, and where each village or town can be considered a source of possibilities for creative cultural tourism.

However, the ephemeral existence of CREATOUR is perhaps its main limitation – it was a project that last just 3 years. In order to actively support creative tourism initiatives, a permanent institution or agency with the same goals as CREATOUR should exist. Without institutions offering a permanent support to creative projects that are scattered throughout the territory, it is very difficult to keep alive the flame of innovation and entrepreneurship in low-density territories. Therefore, as mentioned above, without the systematic support of governments and public authorities (who do not haggle over support for mass tourism) it will be very difficult to reverse the situation with regard to the consolidation of soft, smooth, alternative tourism. Just as a plant that is still very tender has to be treated and protected from the bad weather, so smooth forms of tourism have to be protected and cherished by the public institutions that exist to look after the common good.